Image: King Arthur’s Round Table on the wall at Winchester Cathedral. It is an imitation from around 1300 A.D., later painted under the Tudor King Henry VIII – note the Tudor Rose in the middle. The table has space for 25 people.

Origins

The Arthurian legend was popularised in England and France during the Middle Ages, but Welsh accounts go back much further. The backdrop for the tale is the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Romano-Celtic Britain. Amongst English speakers, If you mention the sword in the stone, the lady of the lake, or the knights of the round table it will immediately evoke images of a heroic and chivalrous age, with sorcery and battles, both physical and moral. The legend captured the imagination of the medieval world. Indeed, an imitation of King Arthur’s famous round table may be found hanging in Winchester Cathedral today. It is believed to have been constructed in 1290 for a tournament to celebrate the betrothal of Edward I’s daughters, but it may be slightly younger. It was ordered painted by Henry VIII to honour a visit by the Holy Roman Emperor. In medieval times, it was thought authentic.

The Arthurian stories waned in popularity after the medieval period, before experiencing a resurgence during the Gothic revival of the 19th century. In 1927 at Tintagel (a site associated with Arthur’s birth), the Order of the Knights of the Round Table Home – The Fellowship of the Knights of the Round Table of King Arthur was formed to promote Arthurian notions of Christian chivalry as a model for modern-day ethical modes of behaviour. Avalon Isle, where Arthur was laid to rest, is associated with Glastonbury Tor (tor is Celtic for hill). Today, the tor is connected with new age movements and the immediate countryside has hosted the Glastonbury Festival since 1970.

Strangely, the Arthurian story does not concern the English as protagonists, as they were most certainly the enemy in the legend. Yet Arthur has been adopted as one of their own, with so much water under the bridge. The story may concern an actual ruler around 500 A.D., defending his territory from the invading Anglo-Saxon horde. While much of the story is certainly myth, it has had a profound effect on the English-speaking peoples of the world. Monty Python’s version in the 1970s, took a great deal of poetic licence with the story, but perhaps no more than some medieval writers. The Camelot novellas and movies of the 50s and 60s, laid on the schmalz a little too heavily.

Geoffrey of Monmouth first brought Arthur into European literature in the early 12th century through his immensely popular History of the Kings of Britain and this often serves as a starting point for later writings. Crestien de Troies wrote a handful of romance poems associated with the legend in the late 12th century, ostensibly based on Welsh sources, adding Lancelot, Camelot, and the Holy Grail quest to the story. The first English-language prose was by Sir Thomas Malory, which recreated Arthur as a 15th century hero. The Death of Arthur was printed by Caxton in 1485. While details vary widely from account to account, there are several timeless themes within the myth.

Right to Rule – not by force:

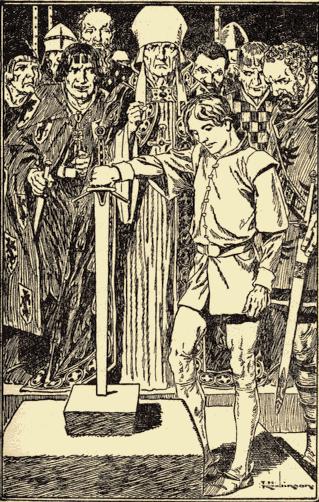

The story begins with Arthur born the illegitimate son of the King of the Britons. He is raised in secret away from public view. While Arthur is still a boy, the old King dies. In the days before courts of law, a physical challenge called an ordeal was seen as a way to reveal God’s will. In the legend, to gain the throne, aspirants had to demonstrate that they had the right-to-rule by withdrawing a sword from a stone, in which it is deeply embedded. Many come forward to try, but all are thwarted in their attempts to withdraw the blade. Try as they might, no amount of force will wrest the sword from the stone’s vice-like hold.

The young Arthur then requests an attempt and is brought forward, no doubt to some ridicule. Arthur gently takes the grip, then quietly persuades the sword from the stone. The assembly is astonished and then kneel before their King. In some ways, there are echoes the Aesop fable of the North Wind and the Sun in this.

Chivalric Code:

The knights in Arthur’s service were required to swear a sacred oath as their bond. In Malory’s English version, this chivalric (from the French for the horse, which heavily armoured knights rode) code may be summarised as follows.

- Never commit outrage nor murder

- Always turn from treason

- Be not cruel but offer mercy, if mercy is requested

- Give assistance to ladies, gentlewomen, and widows

- Never harm ladies, gentlewomen, or widows

- Fight only for God and Country, not for material things

- Fear God and maintain His Church

Equality – The Knights and the Round Table:

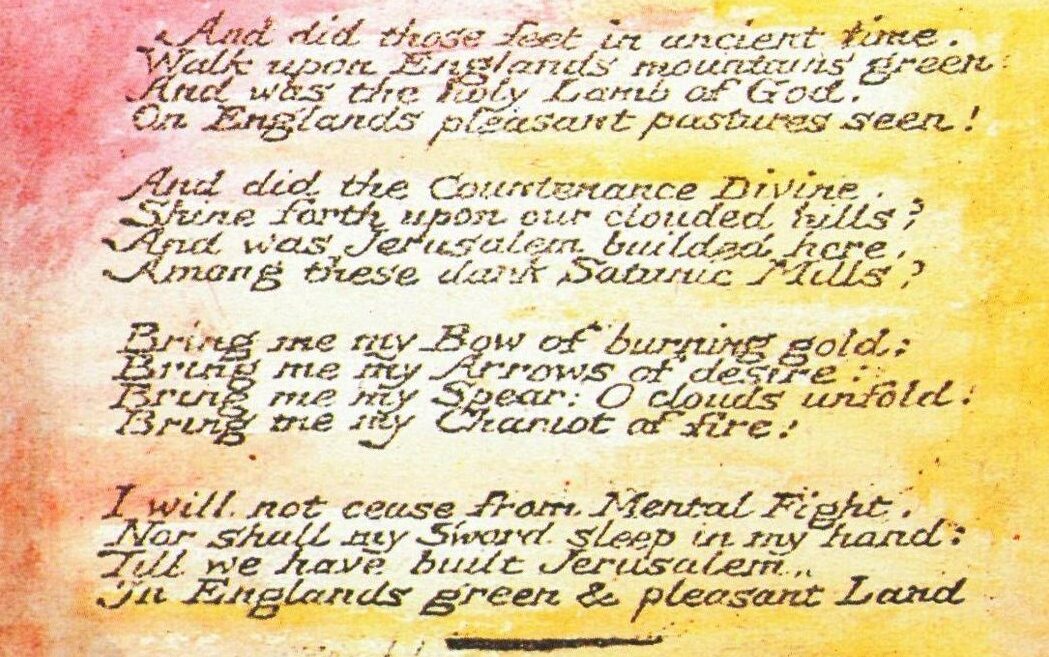

In the French version of the legend, the knights are an order dedicated to defending and keeping the peace in Arthur’s realm. Later, they embark on a quest for the holy grail, which had been entrusted to John of Arimathea at the last supper. Indeed, English folklore says that John visited Britain in the 1st century A.D. when it was under Roman occupation, spreading early Christianity. The poet Blake alludes to this in a preface to an epic poem which, when set to music by Parry and orchestrated by Elgar, has become the English Patriotic Anthem Jerusalem.

King Arthur ordered a table to be made for the knights to meet. It was made round, so that there could be no discussion as to who had the most honoured position at the table. The number of knights at the table varies greatly from version to version – from a dozen to well over one thousand but most commonly a few hundred seats. The Winchester Round Table features 24 knights, plus King Arthur. Despite the high symbolism of the table, with time the knights split into factions and conflict arose.

The principle is clear. All knights, whether high sovereign or low noble, are united and equal in their sacred mission. The knights are from all over Britain and also from the far reaches of the former Roman Empire. Some knights are known from early Welsh folklore, while others appear first later. In the French chivalric romances, these knights are the focus of eponymous works. Sir Galahad is the perfect knight, illegitimate son of Sir Lancelot, known for his gallantry and purity. He is the only one God deems worthy to find the grail. Mordred is Arthur’s son who later betrays him, attempting to usurp him while Arthur is on the quest for the grail. Lancelot is a close companion of Arthur and a great knight but is flawed. He famously has an adulterous affair with Arthur’s own Queen Guinevere, and his quest for the holy grail suffers for it. Tristan who accidentally consumes a love potion, falls in love with Iseult and spawns a Wagnerian Opera.

Spirits of Sacred Waters:

As King Arthur lies dying, he asks his trusted knight Sir Bedivere to throw Excalibur into a nearby mystical lake. On his return, Arthur queries the knight to see if he has done as requested. Arthur asks, “What did you see?” Upon which Sir Bedivere remarks that he saw nothing unusual. Arthur then bids the knight to return to the lake and do as he has requested. Sir Bedivere returns to the lake. The previous time he was unable to part with such a mystical weapon, but this time he casts the sword far out into the waters. Before the sword breaks the surface of the lake, it is caught and held aloft above the water by the hand of a water spirit – the Lady of the Lake. Later, as Arthur is being transported by boat to Avalon, the Lady of the Lake appears again to assist in his final journey.

Excalibur had been granted to Arthur by a water spirit some years earlier, in return for only one favour, after his own sword had been damaged in battle. Accompanied by the sorcerer Merlin, Arthur had rowed out into the lake to receive the magical sword from the Lady of the Lake (a different spirit). In return she asked only for the head of one of Arthur’s knights, Sir Balin, as he had wronged her. Arthur refused and, upon this refusal, Sir Balin instead swiftly beheaded the water spirit, to the horror and shame of Arthur. He immediately banished Sir Balin.

As much of the fenland of Britain has been drained in modern times, many swords have been recovered from what were once boggy marshes and lakes. Indeed, even many simple hills today, such as Glastonbury tor, were once islands in shallow watercourses. For the Celts, these votive offerings were for the goddess of the waters, the goddess of healing. Indeed, many early Christian Churches in the British Isles were built near ancient votive offering sites. In various retellings of the Arthurian tales, there is sometimes one and sometimes many water spirits with varying qualities and known by various names, Nimuie, Nynyve, Viviane, presumably based on the names of original Celtic spirits.