(Motto: “Orta Recens Quam Pura Nites” Newly risen, how brightly you shine)

Autocratic Origins

For more than thirty years, appointed Governors (Phillip, Hunter, King, Bligh, Macquarie, and Brisbane) exercised powers in the colony of New South Wales (N.S.W.) which exceeded those of the King of England. These powers would have been illegal in England unless ratified by an Act of Parliament. The Governor made Proclamations, which were then posted around Sydney Town on the doors of storehouses, affixed to trees and, from 1803, published in the Sydney Gazette. At that time, though an undesirable situation, it was a pragmatic solution since there were only convicts with no civil rights, as well as soldiers and civil servants. It must be remembered that at this time, very few men had the right to vote in England. It was not until 1832, that voting was extended to men who met a modest property threshold.

The winds of change would come as convicts received their certificate of freedom, usually after 7 years, children began to reach adult age, and the number of free settlers began to outnumber the number of convicts transported. By 1812, twenty-four years after the founding of the colony, the new colony was agitating for full civil rights from the British Government. In 1819, the Australian born (known as a currency lad) William Charles Wentworth published “Description of the Colony,” in which he demanded both an elected Legislative Assembly and an appointed Council, to take over taxation. He warned that the fledgling colony might begin dialogue with the United States. The colonists took action in the form of a public meeting and, on the 22nd March 1819, a petition supported by 1260 people was despatched to London.

Representative Rumblings

Meanwhile, the British Government had already begun to take action, appointing John Thomas Bigge to report on the condition of the colony. On reading the report, the Government in England passed an Act in 1823 to create a council of five to seven members, to advise the Governor. This was extended in 1828 to include seven official and seven non-official members. All were appointed, and the colonists had no say in who should serve. At this point in time, the colony of New South Wales was forty years old.

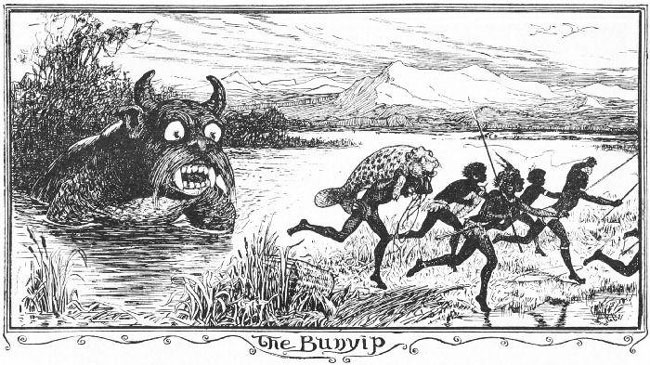

Transportation of convicts ceased in 1840. A Bill was prepared by Lord Russell, and passed the English Parliament in 1842, to create a Legislative Council of thirty-six members, of which twenty‑four were to be elected and twelve appointed. This was moving towards representative government, but still not yet a body fully responsible. In 1851, Wentworth insisted that the N.S.W. Legislative Council send a “declaration and remonstrance” to London. The reply came to “draw up your own Constitution.” The Constitution drawn up by Wentworth was placed before the Legislative Council in August 1853. It was generally accepted, but Wentworth’s proposal for Lower House electorates which would favour squatters, and an Upper House consisting of hereditary peers as in England, was rejected. Opposition came from Henry Parkes and John Darvall. The idea of peerages was singled out for particular derision with Daniel Deniehy describing it as a “Bunyip Aristocracy,” the bunyip being a dreamtime creature found in swamps and billabongs.

The N.S.W. Constitution

The Constitution received Royal Ascent from Queen Victoria on the 16th July 1855. Not a single revolutionary shot was fired. The new Parliament sat for the first time on the 22nd May, 1856. The first Premier was Stuart Donaldson. The Upper House or Legislative Council was to consist of no fewer than twenty-four members nominated by the Governor on advice from the Executive Council. There were no property requirements, but public servants could not be appointed. The Lower House or Legislative Assembly was to consist of fifty-four members elected from the pool of qualified voters.

Excluded from voting were office holders under the Crown, public servants, military officers, or ministers of religion. Voters had to be men over twenty-one years of age, with a rather modest property requirement of £100. Indigenous men had full voting rights in New South Wales, if they satisfied the requirements. In 1858, the £100 threshold was removed, and the franchise was extended to nearly all men, provided they had been in the colony for at least three years. Strangely, if a man qualified in several districts, he could vote more than once. Plural voting was abolished in 1893.

At Federation in 1901, all who had a state level franchise could vote and stand for office in federal elections. Also in the Electoral Reform Act of 1858 was the secret ballot, a voting system pioneered by Victoria and South Australia. So revolutionary was it, that it was known around the world at the time as “The Australian Ballot.” Women obtained the vote in N.S.W. and at a federal level in 1902. They could become members of the Assembly in 1918.

All members are required to swear an oath of true allegiance to the reigning Monarch of N.S.W. who, in 2021, is Queen Elizabeth II. The oath is extended to her heirs and successors. Those who cannot truly make this solemn oath, are not qualified to serve the people of New South Wales.

Federation

At Federation, N.S.W. gave up responsibility for defence, customs and excise, coinage, and postage to the Commonwealth powers specified in the Australian Constitution. A new N.S.W. Constitution was passed in 1902, and the number of members in the Legislative Assembly was reduced to ninety to account for the narrower remit. Of thirty-two new members of Federal Parliament created for N.S.W., twenty-seven had been in the state-level Parliament. These included the first Prime Minister, Edmund Barton, as well as four others who later became Prime Ministers: John Watson, George Reid, Joseph Cook, and W.M. Hughes.

Voting System

At the beginning of the twentieth century, voting for the Legislative Assembly was by “first past the post.” This had the disadvantage that someone who may receive the most votes may also be disliked heartily by a majority of voters. Various systems were experimented with until, in 1928, the preferential system was brought in along with compulsory voting. In preferential voting, if no candidate has a clear majority, the candidates who have too few votes to win are removed and the preferences on their ballots are assigned to the other candidates until a clear majority is obtained. In this way, the candidate who is disliked least by most should win.

Crisis

In 1932, N.S.W. saw the only dismissal of a Premier via the reserve powers of the Governor. As the depression bit hard, N.S.W. defaulted on foreign debt (primarily acquired for the Sydney Harbour Bridge). The Federal Government intervened, paid the interest for N.S.W. and passed a law to recover it from the state. The Premier, Jack Lang, ordered the state public service not to comply. The next day, the Governor of N.S.W. Sir Philip Game dismissed Lang on the grounds that directing state-officials to disobey Federal laws was illegal.