Image: Atlas, the Greek god of philosophy, mathematics and astronomy, holding up the celestial sphere of the universe – 2nd century A.D. Roman copy of Hellenistic original.

The Greeks

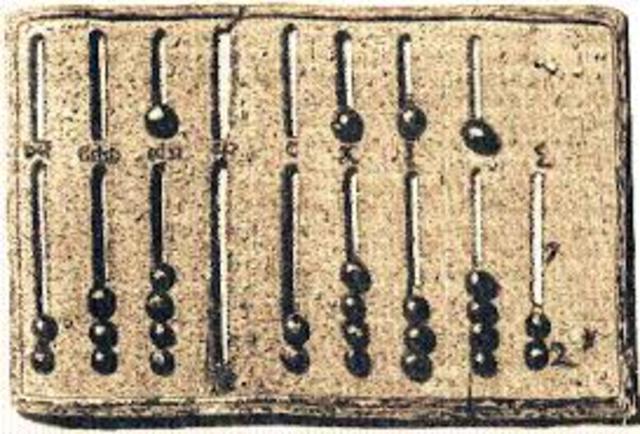

It is Thales (Tha-leez) of Miletus (624-548 B.C.) who is recognised as breaking with the use of mythology to explain natural objects and phenomenon and instead using natural theories and hypotheses (from the Greek for foundation). He used geometry to calculate (from Gk. khálix Lt. calculus – a small pebble used on an Gk. abakon Lt. abacus) the height of the pyramids and the distance of ships from shore. He was the first to apply deduction to create geometrical theorems, including his eponymous theorem. The Thales theorem states that if the three points of a triangle lie on a circle and the hypotenuse is the diameter, then the apex which does not include the diameter is a right angle.

After Thales, the Greek philosophical schools would adopt this approach to understanding the universe. Democritus famously predicted the existence of the smallest indivisible particle of matter. He called this the atom, from the Greek meaning unable to be cut (τέμνω – témnō to cut, plus the negation “a” to yield a-tom). Yet an aspect of the Greek philosophical school which was lacking was that of the inclusion of structured experimentation to test hypotheses, relying instead on thought experiments.

While Greek philosophy was developing mechanisms for obtaining the underlying truth of the world, there was also the rise of the practice of sophistry. The term sophistry today is used to describe arguments which sound convincing but are cleverly created with the intention to deceive. The term sophistry derives from the Greek word for wisdom, but critics, such as Plato, Isocrates, and Aristophanes, sum up the sophists as “hair-splitting wordsmiths.” Yet the sophists did have their uses in the litigious society of Athens if, for instance, you needed to get out of paying a debt.

Islamic Conquest

After the golden age of Greek philosophy, for many centuries there was little progress in the West in understanding the universe. The Romans concentrated on engineering, architectural, and militaristic marvels supported by the work of Greek mathematicians and natural philosophers. They also experimented with ways to govern a vast empire, but not once considered democracy. Then with the fall of Rome, Europe fell into a medieval dark age. The writings of the Greeks were, however, absorbed by the Islamic world who stumbled across libraries from antiquity as they conducted their conquest of Christendom. In 810 A.D. many Greek works were translated into Arabic and then, in centres across the Islamic world, further contributions were made to the body of knowledge. The most well-known of these are al-gebra, and al-gorithm.

The Enlightenment

A new dawn began in the West from the 13th century onwards – notably, with the Franciscan Friar and Englishman Roger Bacon (1214-1292), who placed emphasis on empirical observation. He was the first in the West to write down the formula for the Chinese invention of gunpowder.

Observations of the heavens were important in the middle-ages, mainly for the timing of religious festivals. Yet it was the observations by Brahe of the 15th century that would lead to the heretical heliocentric hypothesis of Copernicus in the 16th century. Before this time, the Ptolemaic view of the solar system had been accepted, that the earth was the centre of the entire universe. In the 17th century, Galileo started making observations of the planets, discovering a system of satellites around Jupiter, observing the phases of Venus, and realising that the milky way (galaxy in Greek) was not a nebulous fog but comprised a multitude of points of light. These, and other observations, led him to hypothesise a less incorruptible heavenly universe and support a sun-centred system which he published in 1632 A.D. This brought him into direct conflict with the Pope. The inquisition, an early form of cancel culture, said that he must recant or die at the stake in flames. After wrestling with his conscience for a short while, he recanted, but the irrefutable truth would not be suppressed for long.

The enlightenment is the period beginning in the 17th century when the works of the Greeks were re-discovered, and the insight of Thales was once again applied to the understanding of the physical and natural world. Yet this time the insights were combined with a crucial addition.

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was an English Philosopher and also Lord Chancellor of England. His birth came shortly after England’s split with Rome in 1533, 12 years after Luther’s appearance before the Diet of Worms. Bacon is lauded as the father of empiricism and for developing the scientific method.

Bacon’s insight would not have been possible without all the enquiry and observation that had gone before, yet the social and political freedom of thought now afforded to the English was also key. His contribution was to assert what has now become known as the scientific method. It differs from the deductive reasoning of the Greeks in two important aspects. It asserts that the truth about the laws and nature of the universe may be obtained by

- induction of an explanatory model based on empirical observation of phenomena and that

- the predictions of the hypothesised model should be calibrated against reality, that is tested against carefully designed experiments to measure deviations between what is observed and what is predicted. If there is a statistically significant deviation, then the hypothesis is either wrong or is only correct in a particular parameter space and needs modification.

This approach was revolutionary. It also asserted that knowledge is universal and the method does not support the notion of multiple truths depending on your epistemological standpoint. Yet, the postmodernists might opine, that the scientific method is just an assertion of one of many methods to obtain one of many truths. Critical Theorists would assert that its only purpose is to maintain hegemony over identity groups, serving solely as an instrument of power. These postmodernist assertions are demonstrably false, while the assertions themselves are purely ideological. They are in the realms of mythology.

The scientific method works. The proof is in the fact that heavier than air machines fly, humans can be propelled to the moon and be returned safely, deadly bacteria can be vanquished, and these words can be carried to you on laser beams, confined to optical fibres, in the blink of an eye.

Bacon’s seminal work was the Novum Organum. One of his biographers, William Dixon, similarly observed in the 1860s that “Bacon’s influence in the modern world is so great that every man who rides in a train, sends a telegram, follows a steam plough, sits in an easy chair, crosses the channel or the Atlantic, eats a good dinner, enjoys a beautiful garden, or undergoes a painless surgical operation, owes him something.”

Lysenkoism

The scientific method is in direct ideological conflict with Critical Theory, including rising ideologically driven movements such as decolonisation. These seek to discredit the scientific method, often by ad hominin attacks or by assertions of power privilege as previously discussed. There is a movement in South Africa called “Science must Fall,” refusing to accept Western science and reverting to traditional mystic beliefs. Yet there is also the rise of the silencing of scientific research which does not agree with the endorsed narrative. Unfortunately for the narrative, the truth often does not lie in consensus, nor does it agree with ideology.

One is reminded of the infamous Soviet agronomist Trofim Lysenko (1898-1976). He rose rapidly through the ranks by denouncing Western biological and agricultural science as Bourgeoise. Amongst many ideologically driven reforms that he introduced was that of planting seeds in tightly nested groups. The ideologically driven belief was that plants would cooperate and share resources more efficiently, if planted in “communes.” His masters loved him for it, his opponents died in the gulags, and the result was that millions of people starved when the crops failed. His lasting claim to fame is that ideologically driven “science” is now known as “Lysenkoism.”