In the north-west tower chapel of Westminster Abbey, where Britain’s great and good are memorialised, there is a bronze bust of Major General Charles George Gordon with downcast eyes. Born 1833. Killed at Khartoum 1885. It is a memorial because his body was never found, slain after enemy forces broke into Khartoum after a long siege.

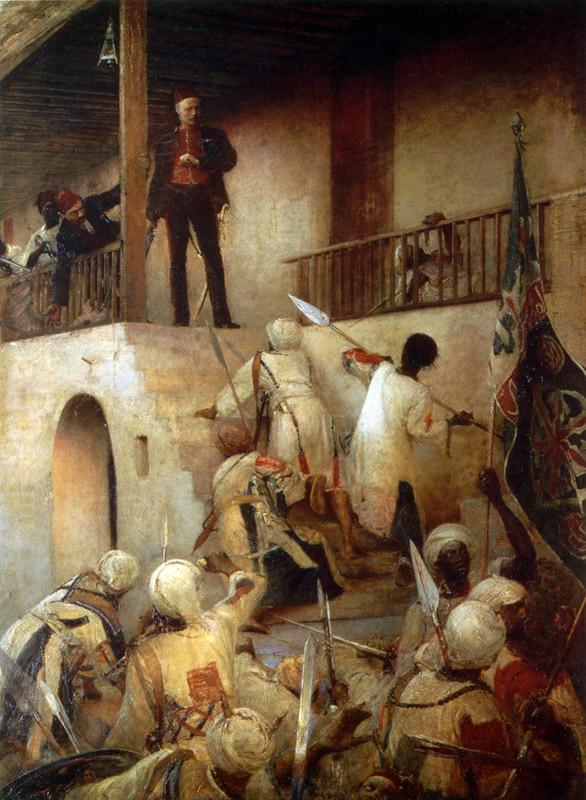

This siege is depicted in the British epic film Khartoum (1966) with Charlton Heston as Gordon and Laurence Olivier as the Sudanese leader whose people proclaimed him as the Mahdi “the rightly guided one.” In the film, both men are depicted as righteous in their respective causes, even unto death. During the film, the pair engage in negotiation, offering each other terms they know the other cannot accept. The Mahdi’s forces eventually storm the city and break into the Governor’s palace. Gordon appears before them on a landing, all falls strangely silent in his presence, until the spell is broken and a spear pierces his breast.

Gordon ultimately lost the defence of Khartoum, why then would he be lauded above nearly all other British Generals?

Gordon was a fifth-generation military man, born to a Major General in London, and moving as a child as his father was stationed at various posts around the Empire. He never considered any other career except soldiering. As a cadet, Gordon was known for high spirits and disregard for rules he thought unjust. Yet Gordon was charismatic, being able to inspire his men to follow him anywhere. He was a religious man fond of St. Paul’s writings “For to me, to live is Christ, and to die is gain.”

In 1855 he was sent to the Crimean War “hoping, without having a hand it, to be killed.” There he earned a reputation as an able and brave officer. After a time in England, Gordon begged to be sent anywhere in the world where there was action. He volunteered to serve in China. There he battled with the Taiping rebels – a civil war which would consume 30 million lives. He was present at the burning of the Summer Palace, regretting it deeply but acknowledging that a measure was necessary after the brutal slaying of British and French officers travelling under a white flag. Gordon, gained the respect of the Chinese under his command as he was honest and incorruptible, not taking a cut of the money due his soldiers, but paying them on time and in full. Gordon was deeply moved by the poverty he saw in China, convinced that God would one day redeem humanity from all this wretchedness and misery.

In 1871 the Khedive of Egypt, while Egypt was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, asked Gordon to proceed up the Nile to Khartoum. Along the way he worked to suppress the Islamic slave trade while struggling with the Egyptian bureaucracy that had no interest in this endeavour, sabotaging his efforts. Gordon grew close to the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and his work gained him a reputation as a saintly man.

The work against the slave trade brought the economy of Sudan into crisis and made Gordon many powerful enemies – most notably Rahama Zobeir “King of the Slavers.” In 1877, Gordon, clad in the full gold-braided ceremonial uniform of the Governor-General of Sudan, rode unannounced into the enemy camp to discuss the situation “leaving the rebels dumbfounded.” They allowed him to leave alive. In 1880 Gordon left Egypt for various assignments all over the world as well as an extended break in London.

a.k.a. Rahama Zobeir “King of the Slavers.”

In1883, Egypt was expelled from the Sudan by the forces of the Mahdi. Egypt had also become a de-facto protectorate of the British Empire in 1882. In early 1884, Gordon was sent to Khartoum to report on the best method to evacuate the Egyptian soldiers, civilian employees, and their families. He left with the firm conviction that this was to “carry out the work of God.” On arriving in Khartoum, he was met by a jubilant crowd crying “sultan.” He announced that on grounds of honour he would not evacuate Khartoum. He did though evacuate the sick, the women, and the children. He began preparations for the defence of the capital whilst he negotiated with erstwhile enemies for support and appealed to public opinion in Britain hoping to force the government’s hand, appalling Whitehall. The government refused to send more troops to Gordon’s assistance. The siege began in March 1884, Gordon maintained morale within the walls with regular performances from the military band.

In August 1884 Whitehall finally ordered a relief to be sent. In September, an armoured British relief steamer was captured by the Mahdi as it coursed along the Nile to Khartoum. All on board were killed, many of whom were affectionately known to Gordon. By the end of the year, Khartoum was starving, and Gordon allowed anyone to leave who so desired it. A last note sent by messenger contained “Can hold out for years.” However, a darker message betrayed the real situation, memorised by the messenger who could speak little English, “Come quickly.” Unlike in the movie, Gordon and the Mahdi never met, but developed a grudgingly mutual respect. Towards the end, it is said that Gordon oscillated between a longing for martyrdom and the intense horror at the prospect of his demise. On the 26th January 1885, the Mahdi’s forces breached the walls, slaughtering all 7000 defenders without mercy.