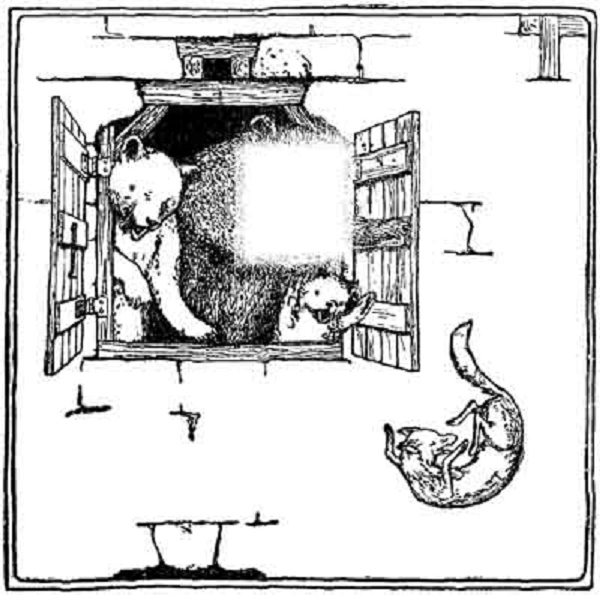

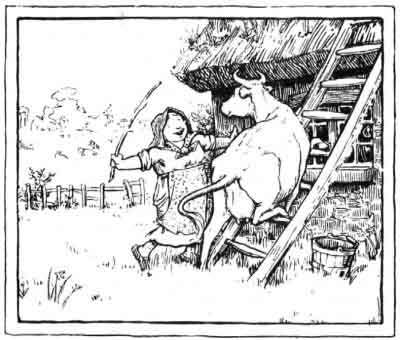

Image: At the behest of the little bear, the three bears toss the fox, called Scrapefoot, out the window. The fox has been sitting in their chairs, drinking their milk, and sleeping in their beds. The other bears wanted to hang or drown him.

In 1854, the eminent folklorist Joseph Jacobs was born in Sydney, New South Wales, though his working life was spent abroad – predominantly in England and the U.S.A. He wished that English speaking children could read tales which had emerged from the folklore of the British Isles, rather than those of the continent made popular by Charles Perrault in the 17th century, and the Grimm Brothers in the first half of the 19th century. Jacobs lamented that Perrault’s genius displayed in Cinderella and Puss in Boots had ousted the English classics of Catskin and Childe Rowland. Likewise, Tom-Tit-Tot had given way to Grimm’s Rumpelstiltschen and The Three Sillies to Hänsel and Gretel.

In his words, while recognising the similarities among stories from different cultures, English language Fairy Tales had become a mélange confus. His concern was for the loss of the cultural memory and folklore of the English-speaking people, as the industrial revolution and its mechanised travel brought the English countryside into contact with the rest of the world. Imagine! This was the era in which one could travel the world in just eighty days! What hope is there then now for the preservation of cultural memory, in an age where information travels around the world on an impetuous Tweet at light speed!

In 1895, Jacobs published the comprehensive English Fairy Tales, containing 43 illustrated stories, later he added More English Fairy Tales. All were designed to entertain and provide life lessons about courage and steadfastness to children, while immunising them against the unpredictability and cruelty of the world. Many are set amongst the everyday sights and sounds of the English countryside, on farms or in hamlets, during famous or mythical times in British History, for instance under King Arthur’s reign or in the time of the hundred years’ war and reign of Edward III. Often there are rhymes embedded within the stories, spoken by magical amphibians or rapacious giants. The “Fee-fi-fo-fum” refrain is common to all English stories of giants and ogres, including in Shakespeare. Apart from ogres and giants, stepmothers abound, and every boy seems to be called Jack. The stories are inevitably extremely violent, with bone grinding action and heads rolling like a Monday morning in 1793 on the Place de Révolution. Yet they end well for the protagonist, with the Scottish ones closing often with “and they never drank out of a dry cappie.”

The mention of just a few tales will, no doubt, bring memories from early childhood flooding back – Jack and the Bean Stalk, The Story of the Three Little Pigs, The Story of the Three Bears (without Goldilocks), Jack the Giant Killer, Henny Penny (about societal catastrophising), The History of Tom Thumb, and Dick Whittington and his Cat. It is beyond the scope of this vignette to go through all the tales, but it is worth highlighting a few, particularly those displaced by the flair of Perrault, Grimm, and Disney.

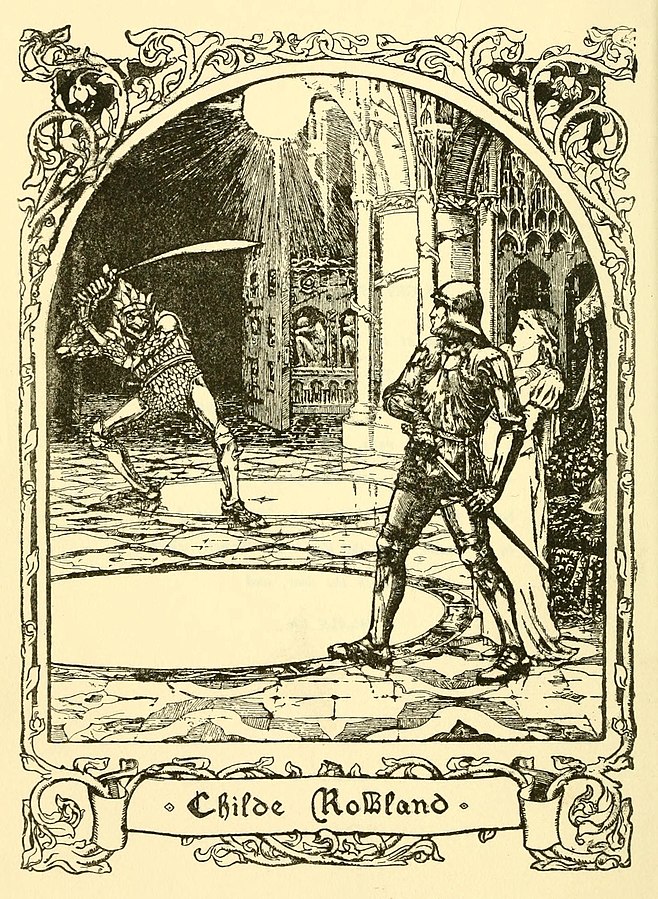

Childe Rowland is the youngest son of Queen Guinevere. The word childe is archaic, yet often found in poetry, meaning a young noble who has not yet earnt his spurs to become a knight. The tale involves spells, and it is his sister, named Burd Ellen, who goes around the church ‘widdershins,’ an Anglo-Saxon word which later writers have interpreted as in a direction contrary to that of the sun (Northern Hemisphere). The Childe and his two brothers seek the help of the local warlock Merlin, who explains that their sister has been taken by fairies to Elfland because she went the wrong way around the church. Merlin then says that it is possible to rescue the girl, but that the bold rescuer must be well instructed, or woe will befall him.

Both elder brothers go to save their sister but neither returns.

The Childe begs his mother the Queen for permission to go. She eventually agrees and gives him his father’s brand (sword, c.f. brandish) which never ever failed his father. He then asks Merlin for his careful instruction. Merlin warns that there is one thing to do and one thing not to do, and both are hard. Childe Rowland must chop off the head of anyone who speaks to him on his journey, while he must not eat or drink anything or “he will never see middle-earth again.”

Childe Rowland dispatches several peasants who speak to him along the way, including an obliging henwife (henwives, keepers of chickens, are associated with the supernatural) who gives him the secret spell to open the door to Elfland. He follows her instruction going three times around a terraced hill widdershins, saying each time

“Open, door! open, door!

And let me come in.”

With this, a door opens in the hillside. Childe Rowland enters a vast bejewelled chamber finding his sister and two brothers under the spell of the King of Elfland. His sister tells him of his impending doom. After his travels, Childe Rowland is famished, and almost forgets that he must not eat anything. He throws the food offered him to the floor. At that moment, the king of the Elves is heard to approach.

“Fee, fi, fo, fum!

I smell the blood of a Christian man,

Be he dead, be he living, with my brand,

I’ll dash out his brains from his brain-pan”

The Elfking appears, “Strike then, Bogle, if thou darest” shouts Childe Rowland (Bogle is Scots for a folkloric creature and cognate with bogeyman). They fight, until the Elfking is defeated and pleas for mercy. Mercy is granted on the condition that all are freed from the spells that they are under and allowed to leave.

Burd Ellen never went around the church widdershins again.

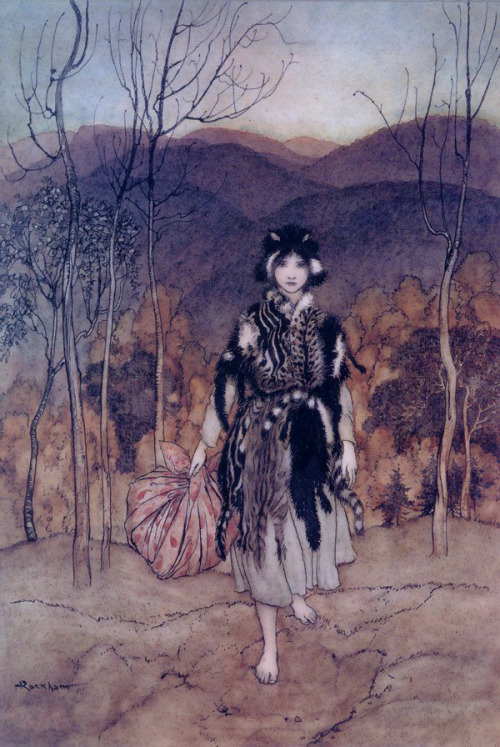

Catskin is the nickname of the daughter of a lord, unloved by her father because he had wanted a boy. The father wishes to marry her off at the first offer. Catskin goes to a henwife who advises her that she should make ever increasing demands for the right to marry her; first a cloak of silver, next of gold, then of feathers of all the birds, and finally a coat made from the skins of cats. In this last coat, Catskin flees and finds refuge as a scullery maid in a castle.

One night there is a ball at the castle, which Catskin asks to attend. The cook is so amused by the peasant girl’s request that he throws a basin of water in her face. Catskin still has her coat of silver from one of the suitors and uses it to attend the ball. The young lord falls instantly in love with her and asks where she is from. She answers, “by the sign of the Basin of Water.”

The young lord holds a second ball hoping she will attend. This time the cook smashes a ladle across her back when she asks to attend. Catskin still has her coat of beaten gold, which she dons for the ball. The young lord of the castle greets her and asks where she is from to which she replies, “by the sign of the Broken Ladle”.

At the third ball, she arrives dressed in a coat of feathers, and hailing from “the sign of the Broken Skimmer” – courtesy of the cook again. This time the prince follows her only to find her changing back into the catskin coat. He tells his mother that he wishes to marry Catskin. The mother is appalled but changes her mind when she sees Catskin in her coat of beaten gold. They marry and a son is born.

When the boy is older, Catskin asks her husband to find out what has become of her father. He finds the father, who is now widowed and alone. The prince asks whether the old man had a daughter. He replies yes and that he would give all he has to see her again. With this, the lord invites the father of Catskin to live in the castle and all live happily ever after.

Tom Tit Tot is an English tale with parallels to Rumpelstiltskin (German Rumpelstilzchen). The story begins with a woman who has left five pies too long in the oven. She asks her daughter to put the pies on the shelf for a while so that they will come again (meaning soften). Her daughter, misunderstanding, thinks that if they are coming again, she may as well eat them now. Later, her mother asks her daughter if the pies have come again. The daughter replies “no.” “Never mind,” says the mother, “I’ll have one now.” The daughter then confesses to eating the lot.

The mother, now quite hungry, sits down and begins to spin flax into yarn, singing about how her daughter has eaten five pies in one sitting. As she sings, the King happens by. While still horrified at her daughter’s actions, but embarrassed too, she changes her song to say that her daughter has spun five skeins of flax today. The King is so impressed, that he asks for the daughter’s hand in marriage. As his Queen, she shall have all that she desires, but one month a year she shall spin five skeins a day or her head will come off. The mother agrees, thinking that by the eleventh month the King will have forgotten about the skeins and the beheading thing.

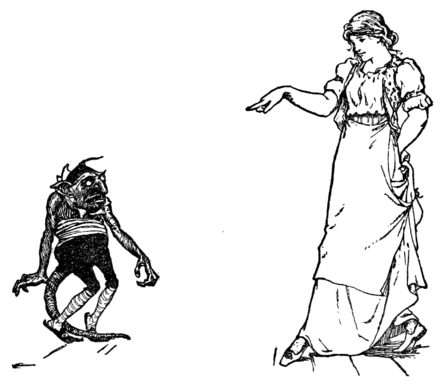

The daughter marries the King and is as happy as can be. Yet after the eleventh month, she is led to a room and told that she will die unless she can spin five skeins a day, she is quite distraught. She has never spun in her life. An elegantly dressed ‘That’ then appears, with a fast-rotating tail. He offers his services to spin all the flax, under one condition: she is to be his, unless she can guess his name. he is a sporting ‘That’ and gives her three guesses each evening. However, many evenings go by, and the Queen cannot guess That’s name. Bill, Ned, Mark, Nicodemus, Samuel, and Methuselah she tries. On the penultimate night, That is filled with glee and looks at her malicefully. It is almost time for the Queen to fulfil her side of the bargain.

Each day the King returns and to his delight five skeins of spun flax greet him. Then one day the King remarks that he has seen a strange creature in elegant dress, spinning flax as fast as he has ever seen flax beig spun, booming away as he worked “Name me, name me not, who’ll guess it’s Tom-tit-tot.”

That evening, the That returns, but this time more confident than ever that he will not be named. The Queen toys with the That, using up two guesses but on the third guess she names him correctly. With this the That lets out a shrill shriek, drops his tail, crumples up his toes, and scurries into the darkness.

The Three Sillies concerns a man who is courting a farmer’s daughter. One evening, the daughter is found crying because she has discovered a mallet lodged in the ceiling beams. She is distraught because she imagines a possible future when she has a child, and the mallet falls killing the youngster. When she explains this to her parents, they begin crying too. With this the man leaves, saying he would never marry into such a silly family.

On his way he then encounters three things much sillier than that of the mallet story. He meets a woman leading a cow onto a roof to eat the grass growing in the thatch. She thanks him when he suggests she should just cut the grass and feed it to the cow. He then meets a man who is trying to jump into trousers held open at the waist by knobs on drawers “how awkward trousers are to get into,” he exclaims, and is amazed when he sees how easy trousers are to get into when you know how. Finally, the man comes across a crowd trying to remove a round object from a pond using pitchforks. The man realises that it is just the reflection of the moon and tries to explain this to the crowd. Yet they won’t listen and so the man leaves as fast as he can.

After these three sillies, the man realises that there are people much sillier than the family of the woman he was going to marry and so returns to wed her.