Australian children encounter Aesop’s fables early on in their lives. Well known amongst a long list of over a hundred titles attributed to him include: The Boy who cried Wolf, The Tortoise and the Hare, The Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs, The Fox and the Grapes, and The North Wind and the Sun. The fables appeal to children because the stories involve many kinds of animals and inanimate objects that speak and solve problems. The tales contain moral lessons for the young and are described as fictional and fantastical stories which also contain truths. His fables contain universal themes of morality that can be found across many early civilisations, and while they differ in detail, they are archetypal truths.

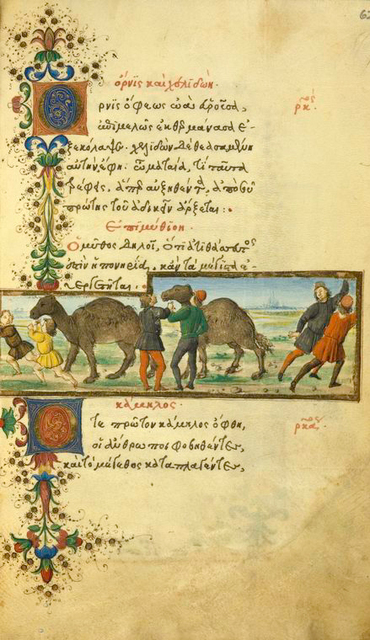

These stories are old, handed down to modern Western nations from the Greco-Roman tradition. They are attributed to a Greek slave named Aesop (Aisopos) who later won his freedom. He had an appearance described as “a faulty creation of Prometheus when half-asleep.” The details of his life are sketchy, containing only what writers of antiquity, such as Aristotle and Herodotus, have passed down. He lived in Greece in the 6th century B.C., probably on the island of Samos. He was executed at the age of 56 in Delphi, on trumped up charges of theft, while on a diplomatic mission from King Croesus of Lydia (Asia Minor). However, the actual reason was that he had caused offence to the Delphians.

The five fables already mentioned are described and interpreted below.

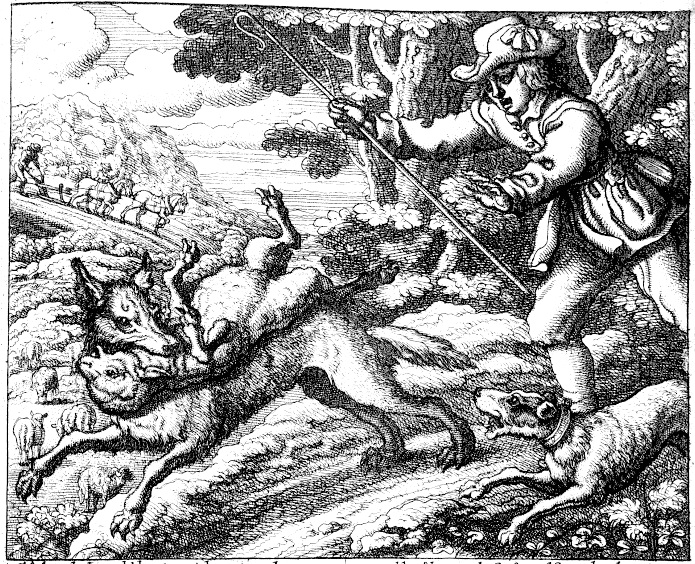

The Boy who Cried Wolf

This fable is one of the first taught to Western children, about the consequences of making impulsive, indulgent, and misleading statements. It made its way into European circulation after it was translated and published in Swabia (modern day Germany) in 1480. William Caxton, the English printer, entitled the story “Of the child whiche kepte the sheep” (1484).

In the fable a Shepherd boy repeatably tricks the inhabitants of a nearby village into thinking a wolf is attacking his flock of sheep. The villagers come to the boy’s aid on two occasions, only to find that it is all just an amusing joke for the young lad. Then one day, a wolf does come for the boy’s flock. He cries wolf, and perhaps more earnestly than any time before. However, this time the villagers won’t be fooled and ignore the boy’s cries. The wolf eats the entire flock, and in a later English version, the boy as well.

It is a cautionary tale about telling the truth. However, it might also be reinterpreted as a warning against narrative creation for political ends. Samuel Croxall (1690 – 1752) asked, “when we are alarmed with imaginary dangers in respect of the public, till the cry grows quite stale and threadbare, how can it be expected we should know when to guard ourselves against real ones?”

The Tortoise and the Hare

The story of the tortoise and the hare is first encountered, in an English-speaking context, in 1667. It was popularised by Walt Disney’s interpretative cartoon of 1935. Some may remember it from The Wonderful World of Disney which was a Sunday evening family favourite on Australian television throughout the 50s, 60s, and 70s.

In the fable, a hare constantly taunts and ridicules a slow-moving tortoise. The tortoise grows weary of the hare’s arrogant behaviour and challenges him to a race. In the contest, the hare soon leaves the tortoise behind and, so confident of victory, takes a nap midway. When he awakes, the hare is shocked to find that the tortoise has, while moving slowly and steadily, already reached the finish line and triumphed.

The fable has attracted conflicting interpretations. The classical Greeks emphasised the hare’s foolish over-confidence. Many people have natural abilities but are ruined by idleness, whereas zeal, steadfastness, and perseverance, in those less endowed with natural gifts, can prevail.

European interpretations have underscored the need for “more haste and less speed,” emphasising the need for careful strategy and implementation rather than rapid deployment based on abstract ideas. A cynical repudiation of this fable’s moral describes the situation in which a bushfire threatens all animals in the forest. In that case, it would hardly make sense to send the tortoise to warn the animals of their impending doom.

The Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs

This fable is sometimes found with the goose replaced by a hen. In English versions, the poultry is nearly always a goose. The English idiom “Kill not the goose, that lays the golden eggs” derives from this fable.

In the English version published by Caxton, a farmer owns a goose which has the remarkable ability to lay eggs made of solid gold. Yet for the farmer, this blessing is not enough and, while an egg a day is assured, he demands that the goose lay two golden eggs a day. The goose replies that, while it can lay one golden egg each day, it is impossible for it to lay two. This reply so enrages the farmer, that he kills the bird. Thus, while wanting to double profits, the farmer now has nothing. In other versions of the fable, the farmer kills the goose to extract the gold stockpile which must lie inside.

In Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971), one room in the factory contains geese that lay golden eggs. A device tests the produce – if the egg is good (golden) then it is shipped out, but if is found to be bad then it is incinerated. Pure avarice in the film is personified by Veruca Salt, the spoilt daughter who wants it all now. After singing about all the things she desires, she inadvertently steps onto the device which tests the eggs and is immediately rejected. She disappears down the chute to oblivion, after which Willy Wonka wryly quips “She was a bad egg.”

This fable has been interpreted as a warning against unbridled greed leading to overreach.

The Fox and the Grapes

In this fable a hungry fox attempts to reach some grapes dangling tantalisingly above him on a vine. He leaps and snaps at the grapes but is unable to reach them. After a while the fox gives up declaring “those grapes were unripe and sour anyway,” intimating they were not worth having. This fable is a lesson for those who talk disparagingly about things they cannot attain. Rather than being honest with himself and admit failure, the fox prefers rationalisation. The dissonance created by desire and frustration leads to ‘adaptive preference formation.’

The fable is the origin of the idiom “sour grapes” in English, when someone is upset with not achieving something and so blames the system, judging panel, or other external cause. The motif of a fox reaching for grapes is found on various household items from the 18th and 19th Centuries, such as pottery, porcelain, candlesticks, and wooden panelling.

The North Wind and the Sun (Boreas and Phoebus)

This fable is often retold, to emphasise the power of persuasion over coercion. In the North Wind and the Sun are squabbling over who is the strongest. The North Wind, confident of victory, agrees to a competition in which each party must try to remove a man’s coat as he walks along. The North Wind begins with strong gusts but is unable to budge the coat. The man tightens the coats belt, collar and cuffs. The North Wind increases the gusts in intensity until they are gale force, but to no avail. The man simply pulls his coat more tightly to his body.

It is now the sun’s turn. With no particular effort, the sun’s rays beam gently down on the man. The man loosens his collar and cuffs. He smiles at the friendly sun as he walks along. After a while, the heat of the sun together with his exertion are too much for the man. He stops, takes off the coat, finds a spot in the shade and rests to cool down. The North Wind is forced to concede that the Sun is the stronger of the two.

Avianus, a Roman writer, summed it up thus “They cannot win, that start with threats.”